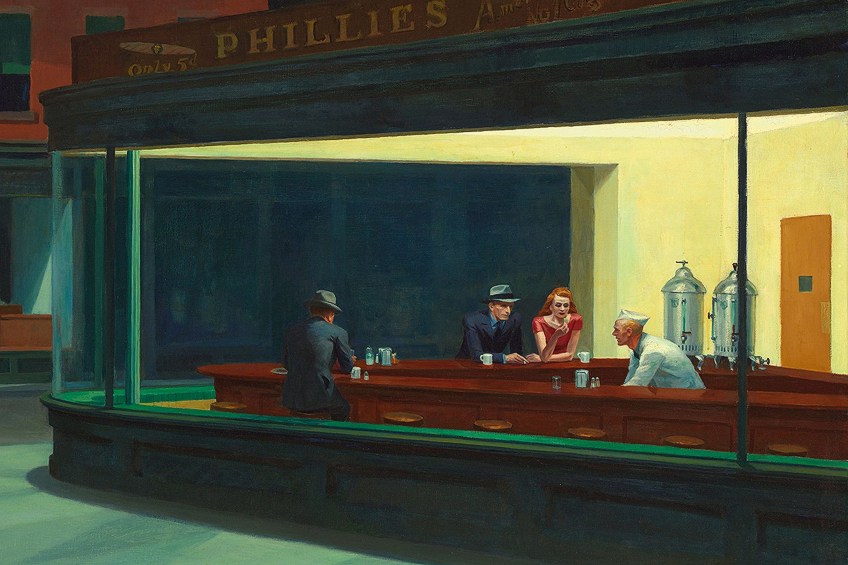

Nighthawks, by Edward Hopper. 1942.

Recall the first time, or the hundredth, that you recited physical exam findings to your professor, noting every detail you could recollect of the brief practice encounter minutes beforehand. Preoccupied with avoiding awkward pauses and giving the “correct” order of findings—What was the name of that final breath sound, again?—pertinent negatives were the farthest thing from your mind. That is, if they were even on your mind to begin with.

Acknowledging the absence of an attribute is a skill unto itself, one that is infrequently practiced prior to the rigors of medical school. Far from being a talent left solely to the realm of medicine, however, understanding pertinent negatives has broad reaching, functional applications throughout life. In any role, art serves as an excellent tool through which to recognize and articulate what often remains unseen.

Nighthawks

A quintessential artist of American Realism, Edward Hopper’s oeuvre encapsulates themes of timeless isolation that are as pertinent today as they were in the 1940s when Nighthawks was painted. His subjects, often physically sharing the same space, are seemingly caught within their own emotional turmoil unbeknownst to the world around them. This painting, completed in the midst of World War II, evokes themes of wartime separation and anxiety that unfortunately resonate in our modern era.

The tone and atmosphere of this American masterpiece cannot be fundamentally conveyed without commenting on its numerous absences.

A couple occupies the end of the bar, appearing to share this somber evening in each other’s company. Observe the man’s mug, however: it’s bereft of the steam instead found wafting from the woman’s coffee, as if she just entered the glow of the fluorescent lights. Their hands, while seemingly embraced, are inches apart. We’d like to assume they are a pair enduring a night of uncertainty together, yet closer observation may suggest otherwise.

The diner itself is more surreal than natural, possessing a singular entryway, likely into a kitchen. No viable entrance is seen that might lead to the soda jerk behind the counter, or a patron into the establishment. They are hermetically sealed away, with us as viewers left to voyeuristically ponder their individual purposes and empathize in their isolation and contemplation.

While the fluorescence of the diner ceaselessly pulls our eye toward its interior glow, a concerted effort to view the adjacent street reveals the pervasive theme of absence. Half-pulled shades are one of the few indicators that people might occupy this avenue. In fact, what is missing defines the space far more than what is present, with the composition’s essentialist reduction that could place us in any New York street corner.

Approaching the Nuances of Effective Medicine

It’s no wonder this painting pervades popular culture with its generation-bridging motifs. Yet the point is, absences matter, and they provide for a nuanced, refined understanding that spans disciplines.

Recalling that focused medical student reciting their memorized exam, how might their differential change based upon the lack of tachycardia, jugular venous distention, peripheral edema, or numerous other signifiers that might indicate serious pathologies? They may have some years to develop that skill set, but its actualization is fundamental in approaching the nuances of effective medicine.

As the years pass and the student graduates to resident and attending, applying the negatives of the exam becomes routine. Here its depth shines, however, particular when thoughtfully observing behavior, and elements outside the templates physicians grow accustomed to. A new patient may behave outside the norm of what we might expect the “average” person to do, or a colleague might abruptly change daily habits, indicating a more serious personal conflict. Observing these salient shifts, or negatives, allows for timely intervention.

Art as Avenue to Skill

Like the refinement of a thorough physical exam, time and repetition hone the application of analyzing pertinent negatives. While clinical acumen and knowledge create broad differential pools from which to incorporate relevant findings in a report, art provides a complementary avenue through which to sharpen the skill.

As pedagogy evolves, and we study and discover new methods to teach and understand practical skills in medicine, let’s not forgo our creative side just yet. Visualizing and verbalizing what we don’t see is an intelligence unto itself that can be practiced outside of our hospitals and clinics in whatever venue you might choose to appreciate art.

Nick Nemeth, DO, is a physician writer based in Colorado, currently completing additional studies in art history to support and work within the museum space.

Sign up for the “Speak for the Heart” newsletter and never miss a post!

You might also enjoy reading (also by Dr. Nick Nemeth):